When a metering pump is operated, the pumped medium is transported through a hose or pipe. This always results in a certain pressure loss, which affects the achievable flow rate and the maximum achievable back pressure of the pump.

The extent of this pressure loss depends significantly on several factors:

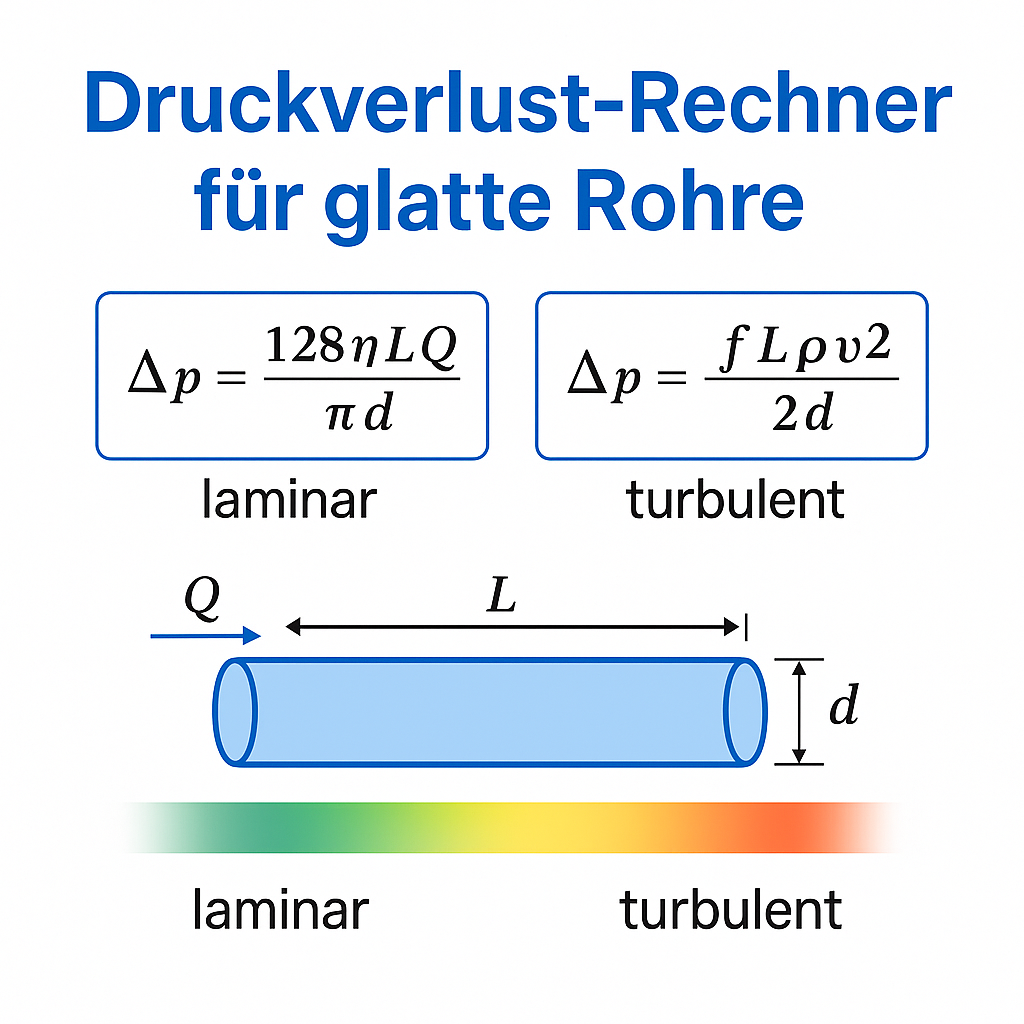

If the flow is laminar, the pressure loss can be calculated exactly using the Hagen-Poiseuille equation. However, turbulent flow occurs in many practical applications – especially at higher velocities, with small diameters, or with low-viscosity media. In these cases, the pressure loss is determined using the Darcy-Weisbach equation, where pipe roughness also plays a significant role.

The following calculator takes both models into account, automatically determines the Reynolds number and indicates which calculation is relevant for the selected application.

"

"

Pressure loss results from friction between the fluid and the pipe wall. Depending on the flow pattern, it is calculated either according to the Hagen-Poiseuille equation (laminar flow) or the Darcy-Weisbach equation (turbulent flow). The calculator on this page takes both models into account and indicates which calculation is relevant for your input.

The flow pattern is determined by the Reynolds number (Re):

The computer automatically calculates the Reynolds number and displays the flow range in color.

Because they apply to completely different flow regimes:

In turbulent flow, pressure losses are significantly higher, often by a factor of 10 or more.

The internal roughness (k) describes how smooth or rough a pipe or hose is. The rougher the material, the more the fluid is swirled – and the pressure loss increases. The calculator provides typical roughness values for:

The Reynolds number is particularly important for metering pumps because small pipe diameters and high flow rates quickly lead to turbulent flow.

That means:

→ More pressure loss than expected

→ Higher load on the pump

→ Lower achievable flow rate

The calculator displays the Reynolds number so you can quickly assess whether a system is operating in the laminar-turbulent range.

As the temperature increases, the viscosity of a liquid decreases. Lower viscosity → higher Reynolds number → flow becomes more turbulent → pressure drop increases. At high temperatures, the pressure drop can therefore be significantly greater than at room temperature.

Many online calculators use different assumptions, e.g.:

The calculator on this page displays both models (laminar/turbulent) and uses realistic inputs, which is why the results are more transparent and precise.

Typical measures include:

Even a small increase in diameter often has a dramatically reducing pressure loss.